I Love Early-2000s Fashion Despite its Flaws

Some Y2K trends were toxic. Can we do them right this time around?

Early-2000s fashions are back! The magazines said so.

Though also the magazines/affiliated digital publications have been sending warning signals on and off for several years now, usually with a tagline like “If Low-Rise Jeans Come Back I’ll End It All I Swear To God” and pictures of Bella Hadid. BUT! The Y2K resurgence is really happening this year. It’s been on the runways, the red carpets, the style TikToks, the FashionNova models. Basically all corners of the clothing market.

I love early 2000s fashion–– like I genuinely and unironically love the aesthetic and I own few pieces of clothing manufactured later than 2008. My personal sense of fashion was shaped by Lizzie McGuire-through-Hannah Montana-era Disney Channel, Teen Vogues stolen from my older sister, and most of all, My Scene dolls. Cut me open and you’ll find rhinestones. I mean it.

Given that, you might expect me to be thrilled to see my beloved fashions getting their due after a decade of slander by 90s-simping minimalists. And I am excited to see so many of you wearing wedge flip-flops again. But my feelings on the sartorial movement are, like the early-2000s themselves, a bit all over the place.

I will attempt to make sense of them here.

The terms “Y2K,” “early-2000s,” and “the aughts” tend to be lumped together, but they all mean slightly different things. The aughts technically refer to the entire decade from 2000-2009, and the early-2000s to just the first part of it. But the world, and fashion, of Obama’s first year in office feels very far removed from when Britney, Madonna, and Xtina all kissed at the 2003 VMAs. The fashion trends we now associate most strongly with the early-2000s— cargo pants, skinny scarves, newsboy caps, Ed Hardy, etc. — were in fullest swing from 2000 through 2006, with some trendsetting late 90s and a bit of bleed into the first season of Gossip Girl.

“Y2K,” literally “Year 2000,” refers specifically to the hullabaloo over the computer meltdowns at the end of the 20th century and the cyber age that was prophesied to dawn with the new millennium. In fashion, Y2K originally described the Matrix-inspired cyber vibe trends that were big from 1998 through the dot-com bubble in 2000. Think these looks:

Today, Y2K is more or less synonymous with “early-2000s,” and I’ve used them interchangeably throughout this essay. Yet the term’s origins are worth remembering. The new millennium was expected to bring big innovations and changes, especially in the communications and media sectors, which were investing more and more in this sick little thing called the Internet. Today we’re all “boooooo Big Tech” but back then it was all still new and exciting. This optimistic, future-forward attitude brought about markedly louder styles and flashier touches than had been seen in the grungy 90s.

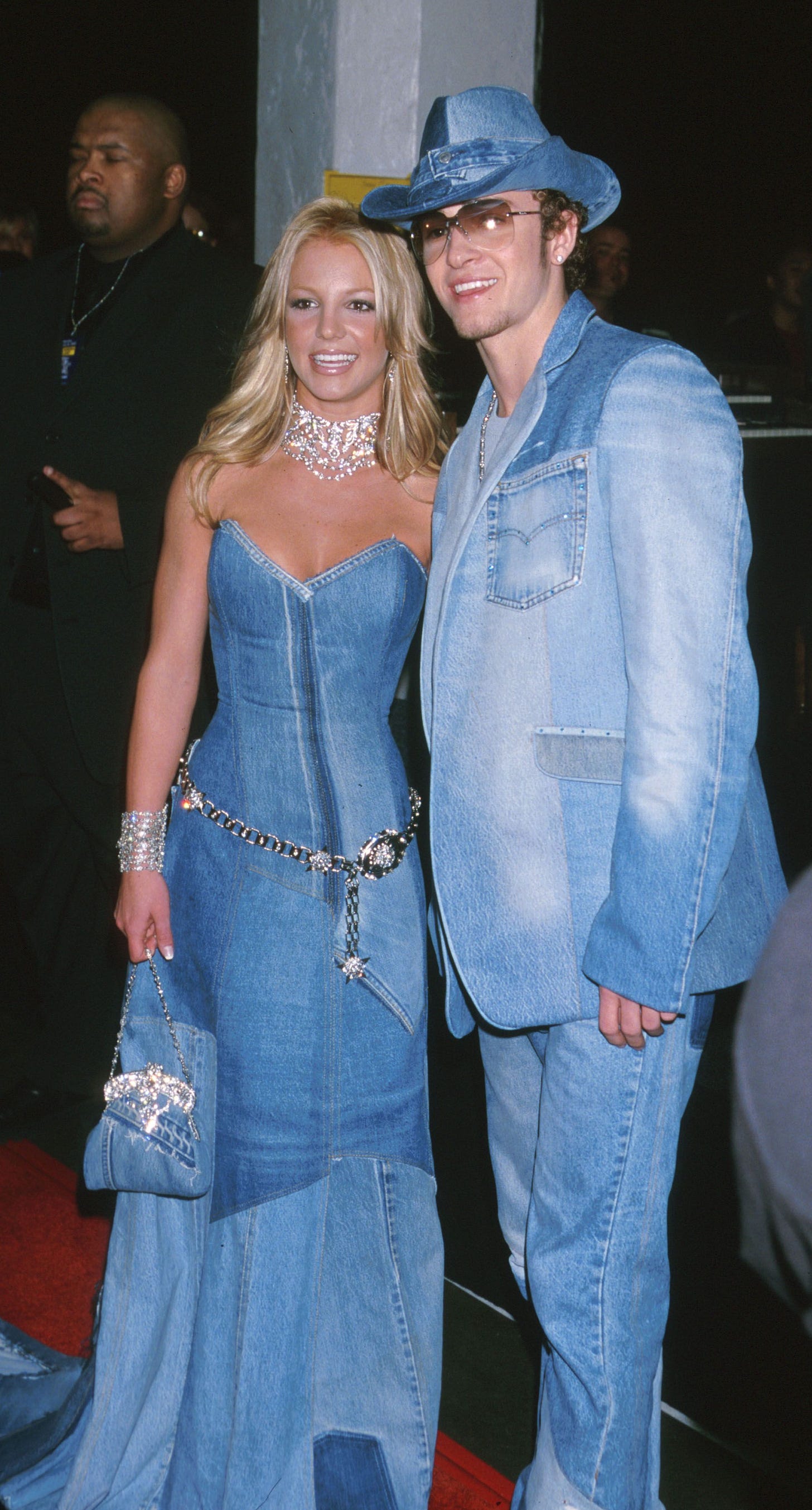

Apart from the brief recession in 2001, the first half of the 2000s saw a boom in spending on durable goods, and fast fashion grew into a dominant position in the global clothing industry. Novelty was in the air, and people started going crazy, as is clear from choices such as this:

With a buffet of options available, “more is more” was the dictating principle of fashion. A floor-length denim gown WITH a denim handbag AND belly chain AND diamond collar AND a gross denim boyfriend? Why not!

Excitable excess is what makes 2000s fashion what it is. It doesn’t care about formality or practicality, god knows it doesn’t care about modesty. It is eye-catching. It’s exuberant. It’s a little trashy. But in the way tequila shots and karaoke are trashy. And tequila shots and karaoke are fun.

It doesn’t surprise me that after the past year and a half of tragedy we’re ready to have fun again.

Remember Bjork’s swan dress at the 2001 Oscars? Of course you do, even if you weren’t alive for it, because that dress made history. Dior paid tribute to Marjan Pejoski’s design in their Cruise 2022 collection, and I wouldn’t put it past Jennifer Lawrence to wear the outfit during next year’s award season.

The way we talk about Bjork’s dress all these years later is different from how we talk about other famous “out-there” red carpet moments, like Lady Gaga’s meat dress or J-Lo’s 2000 Grammy’s outfit, in large part because the swan dress didn’t feel like an orchestrated PR stunt, nor did it seem like peacocking (no pun intended). It just seemed like Bjork really loved the whimsical dead swan tutu frock and wanted to wear it with a bedazzled nude bodystocking and heeled fisherman sandals, and so she did. As Bjork said in response to the ruckus, “it’s just a dress.” So what?

That attitude of “so what?” is what keeps us coming back to those 2000s fashion pics, even though I don’t think we really want to go back to wearing capri-length tights. The trendsetters of the era were so confident in their hodgepodge of sequins and belts that we’re willing to buy it. So even when our heads tell us tubed sweat dresses have no business being paired with pointy neon stilettos, our hearts tell us Hilary Duff looks so dang happy wearing them that we decide it’s really alright.

We aren’t reminiscing over the 2000s with totally rose-tinted glasses, though. In the past few years, there’s been a reexamination of the harmful aspects of the era. The toxic tabloids, the gross mass consumerism, the cultural appropriation, the way we all hated women so much–– those issues feel as endemic to the period as Von Dutch trucker hats.

The aughts were a time of mass consumption and excess, and many style trends were blatant wealth-signaling. There was the logo bag trend, and there were all the brand-name must-haves like Ugg boots, Tiffany charm bracelets, and Juicy Couture tracksuits.

That rubbed people the wrong way even back then. Parents were worried that conspicuous consumption was corrupting the youth and causing bullying, and it didn’t feel good to be a Claire Lyons in a sea of Massie Blocks. There was also concern for the environmental implications of consumer culture, though these were mostly ignored.

Brands like Juicy and Hollister have long since lost their luster, and we’ve lost our appetite for logos as outfit focal points. To be clear, that shift did not come thanks to a social reckoning over the false idols of capitalism, but rather rapid growth in the middle-markets and a flood of quality knock-offs leading to an abundance of luxury goods and therefore the devaluation of name brand products. (I only understand economics as it applies to fashion.)

Now that sustainability is in and average consumers are looking to reduce waste, secondhand shopping is becoming more popular. Conveniently, the wasteful shopping we did in the aughts has led to a surplus of 2000s-era fashions sitting in thrift stores across America. I work in a giant one and every day we put out literally hundreds of donated clothing items that had been sitting unworn in someone’s aunt’s closet since 2005. If you want to get in on the 2000s revival, don’t bother with the cheaply made halter tops on Shein, support your local thrift store. Or your local Depop girl, but you should know she bought that dress at Goodwill for 6.99.

Of course, there is the risk that as Y2K trends come back, those vintage pieces will become too expensive again. But I don’t know. We get a lot of Hollister.

There was a TikTok trend going around this spring where users, most of them Zoomers, showcased what they’d wear as a 2000s pop star. The TikToks reference 2000s pop stars because pop stars were the torch-bearers of Y2K fashion, and they were the torch-bearers of Y2K fashion because photos of them at events, on the streets, in their homes, having their privacy invaded again and again, were plastered everywhere, and are captured forevermore in the amber of Google Images.

Gen Z is mostly too young to remember the early 2000s and is certainly too young to have been scarred by Ed Hardy prints and the smell of Uggs in the summer. Gen Z also missed the worst of hypercritical, scandal-sniffing, rabid trash media culture. It was awful. There’s no way around it. The media went after female celebrities like piranhas and the world couldn’t get enough of the bloodshed. The public abuse of Britney Spears’ enabled the private abuse she has been enduring for decades, and is finally eliciting the outrage it warrants. Earlier this year, a documentary on the grand princess of early 2000s fashion Paris Hilton peeled back the curtain on her famous party girl persona and showed she had been a young, traumatized woman who was exploited by the media and the machine around her. Better to be realizing this late than never, but serious damage was done in the early 2000s.

You couldn’t get in line at the grocery store without passing zoomed-in pap photos of an A-lister’s cellulite stacked between the Mentos and Soap Opera Digest. Drew Barrymore was “fat” and Victoria Beckham was “scary thin,” placing the range of acceptable body sizes somewhere between skinny and very skinny but no skinnier. Britney Spears’ abs seemed to be her go-to accessory on and offstage, and when her stomach was slightly less chiseled at the 2007 VMAs (less than a year after back-to-back pregnancies and in the middle of a mental health crisis, mind you), she was excoriated for it.

To be clear, we are all still pretty obsessed with celebrities’ appearances, and the impact social media has had on body image is a whole other beast and maybe I’ll go into its mouth in another post. But it’s fair to say the extreme viciousness with which the weights, shapes, and appendages of female celebrities were publicly scrutinized and speculated upon during the aughts was a special kind of toxic.

If you lived through that toxicity, and remember the widespread fascination with the virginities of teenage Disney stars, and the gossip mags that called called Nicole Richie fat one week and anorexic the next, and when Ashlee Simpson’s nose job became national news, you may be ambivalent about returning to whale-tales and belly piercings. For this I would not blame you. The 2000s were a fatphobic time, and those of us who experienced that fatphobia may have a hard time separating it from the clothing of the era. I saw an anti-2000s fashion tweet making the argument that the whole point of the aesthetic was for skinny people to show off how skinny they are. It’s even been suggested that Y2K fashion was responsible for eating disorders, as though rates of mental illness rise as waistlines fall and vice versa.

I do understand the hesitancy towards low-coverage Y2K trends. I had it myself. When I was six, I decided to be a tomboy. It was a fully conscious choice. I was a fat kid, and I had started getting made fun of for my weight. One day I went shopping and picked out all the low-rise options and tight-fitting shirts that I thought were so cute on the mannequins, but when I tired them on, I felt greasy, like I needed to be blotted with a paper towel.

I thought I was too fat to wear the clothes I really wanted to, so I decided to dress in baggy t-shirts and basketball shorts full-time. The outfits I yearned for were not the body-bearing getups we associate with Y2K–– hello, I was in elementary school–– they were just attention-grabbing, with sequins, bangles, counterintuitive layering, laces where zippers should be, and zippers where purses should be (remember those?), and I didn’t want to wear anything that called attention to my appearance.

When the business-casual styles of Obama’s first term started popping up, I jumped on board. I got a little navy blazer in fifth grade and thought it was so chic and flattering. I praised god for the thigh-slimming powers of skinny jeans. But I didn’t really love a lot of those trends. They weren’t sparkly enough. They didn’t have enough patterns.

There isn’t anything wrong with wanting to wear clothes that are flattering, nor is there anything inherently wrong with Obama-era fashion (except the trend with the vests over T-shirts, that was always dumb). But we should wear clothes because we like them, not because they cover up the parts of ourselves we think are ugly.

When I was twelve, I developed anorexia, and it wasn’t until I recovered, when I was sixteen, that I felt comfortable enough to wear the kinds of wild clothes I’ve always been drawn to.

I want to be clear here. The hyper-critical, appearance-obsessed atmosphere of the early 2000s was toxic and did contribute to body dissatisfaction, especially among youth. And there is some truth to the idea that 2000s fashions were appealing because they were unattainable. But… that’s true for a lot of fashion. And unlike trends that are cost-prohibitive, or literally illegal for certain citizens if we go back to the time of sumptuary laws, people of all shapes and sizes can wear skimpy clothing. I understand that is much easier said than done, and dismantling fatphobia is going to take time. But if I’d seen TikToks like this when I was seven, I probably wouldn’t have been too ashamed to wear those camisoles with sparkly lace necklines.

All of these issues around 2000s fashion come with a massive caveat: fashion is always influenced by its social and political context, for better and for worse. The clothes and styles people are drawn to reflect their values, concerns, and their indiscretions. Corsets, which are also having a moment, have tightened and loosened with gender expectations since around the fifteenth century, and despite what some TikTok historians may have you believe, the practice of tight-lacing (which shaped the abdomen much more forcefully than the stays of the Regency era, for example) was physically restrictive and medically inadvisable. It is no wonder then that the practice peaked during the Victorian and Edwardian eras, time periods that were defined by restrictive attitudes towards gender and ill-advised medical practices.

Does that mean the current corset trend is anti-feminist? No. They’re tops. It must be possible to wear retro styles of clothing without perpetuating social problems they from the eras in which they were first worn. Otherwise, we’d all go naked.

I have a tender hope for the early-2000s comeback, that it may be more than just a revival, but a Y2K renaissance. A movement that is more inclusive, more environmentally friendly, and more welcoming than the first time around. The spirit of 2000s fashion is fun and shameless, and sparkly. We can channel that spirit and leave the dark side of the era in the past. I hope.